In the gilded halls of Hollywood’s Golden Age, no star was more meticulously crafted, and no icon more mysterious, than Marlene Dietrich.

Most stars of the 1930s were marketed as “America’s Sweethearts” or “The Girl Next Door.” Dietrich was different. She was the “Other.” She was exotic, dangerous, androgynous, and untouchable.

But when I analyze her career for Celebrimous, I see two distinct stories. First, there is the Artistic Creation: the collaboration with director Josef von Sternberg that revolutionized cinematography. Second, there is the Human Reality: the woman who took that manufactured fame and weaponized it against Adolf Hitler.

Her life is a profound study in duality: the manufacturing of an icon, and the forging of a hero.

Part 1: The “Pygmalion” Project (1930–1935)

When Josef von Sternberg arrived in Berlin in 1929 to cast The Blue Angel, he wasn’t looking for an actress. He was looking for clay.

Dietrich was then a cabaret singer—described by critics as a “plump, pretty dumpling.” She was raw. But von Sternberg saw something else: a capacity for stillness. He brought her to Hollywood and began a seven-film collaboration that remains the most obsessive actor-director partnership in cinema history.

The Technical Secret: “Butterfly Lighting”

If you are a student of cinematography or photography, Dietrich is your textbook. Von Sternberg didn’t just light the set; he lit the face.

He developed a technique now known as “Butterfly Lighting” (or Paramount Lighting).

- The Setup: He placed the main key light high above the camera, directly in front of Dietrich’s face.

- The Effect: This cast a small, butterfly-shaped shadow directly under her nose. More importantly, it cast shadows under her cheekbones and jawline.

- My Analysis: This lighting “sculpted” her face. It made her cheeks look hollow and her eyes look heavy-lidded and mysterious. It transformed a healthy German girl into a spectral, ethereal goddess. It was an optical illusion, but it became the gold standard for glamour.

Morocco (1930) and the Tuxedo Moment

In their first American film, Morocco, von Sternberg made a decision that would ripple through pop culture for a century. He dressed Dietrich in a man’s tuxedo and top hat.

In the scene, she performs a cabaret number, strides into the audience, takes a flower from a woman, and kisses her full on the lips. Why this matters: In 1930, this was nuclear. She wasn’t mocking masculinity; she was owning it. She established an image of “audacious gender ambiguity” that made her an icon for the LGBTQ+ community decades before the term existed. She proved that “glamour” wasn’t about dresses; it was about power.

Part 2: The Hero in the Mud

The partnership ended in 1935. By then, the Nazis had risen to power in Germany.

This is where the story shifts from “film history” to “world history.” Hitler and his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, were desperate to bring Dietrich home. They wanted her to be the face of the Third Reich’s cinema. They reportedly offered her a blank check, total creative control, and a royal welcome in Berlin.

Her response: She not only refused; she applied for American citizenship. She called Hitler an “idiot” and declared war on her homeland.

The OSS and “Musak” Propaganda

Dietrich didn’t just pose for photos. She went to work for the OSS (the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA).

She participated in a project called “Musak,” recording songs in German that were broadcast over the radio to weary German soldiers on the front lines.

- The Strategy: She would sing nostalgic, sad songs (like “Lili Marleen”) to make the soldiers homesick. Then, in between songs, she would slip in subtle anti-Nazi messaging, urging them to wonder why they were dying in the Russian winter while their leaders sat in warm palaces.

- The Risk: If she had been captured, she would have been executed as a traitor to the Reich. There is no doubt about this.

The USO Tour: Glamour on the Front Lines

While other stars visited base camps miles from the action, Dietrich insisted on going to the front. She toured North Africa, Italy, and France with the USO. She traveled in jeeps, slept in frozen tents, and washed her iconic legs in helmets full of snow.

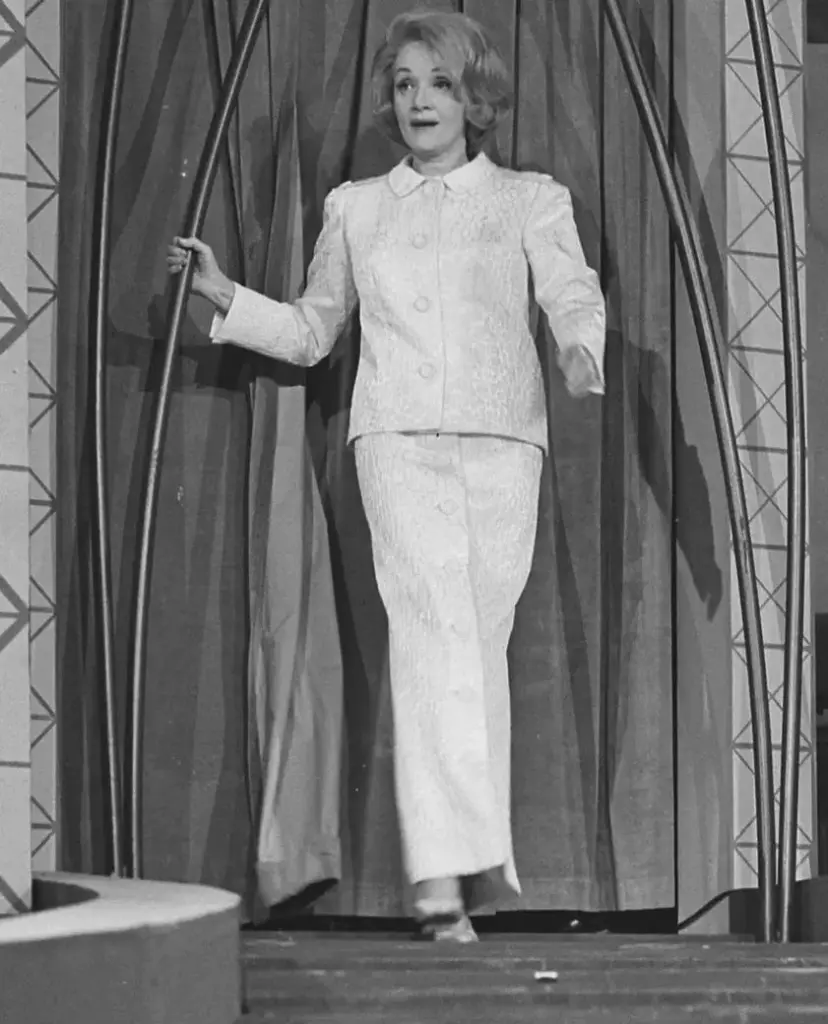

A Personal Observation: There is a famous photo of Dietrich in 1945. She is not wearing furs. She is wearing a rugged army jacket, helmet, and combat boots, holding a captured Nazi pistol. Her face is tired, stripped of the “Butterfly Lighting.” To me, she looks more beautiful there than in any von Sternberg film. That is the face of a woman who found her purpose.

When General Patton met her in Europe, he reportedly told her, “You’re constantly at the front. You’ll be killed.” She replied, “But the boys are here.”

The Price of Integrity

After the war, Dietrich was awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom and the French Légion d’honneur. But she paid a heavy price. She was branded a traitor by many in Germany. When she returned to perform in Berlin in 1960, there were bomb threats and protesters chanting “Dietrich go home.”

She didn’t care. When asked about her life later, she was dismissive of her Hollywood career. She stated simply, “The only important thing I’ve done is the war work.”

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy

Marlene Dietrich’s legacy is one of defiant duality.

She was the ultimate “manufactured” star, a testament to the power of artifice, lighting, and costume. She taught Madonna, Lady Gaga, and RuPaul that you can construct your own reality.

But she was also a woman of profound substance. She proved that you can wear the mask of a goddess and still have the heart of a soldier. She used the fame von Sternberg gave her to fight the greatest evil of the 20th century.

Final Verdict: In 2026, we often talk about “influencers” using their platform. Marlene Dietrich wrote the rulebook. She showed us that a platform is useless unless you stand for something. She was the most beautiful woman in the world, yes—but she was also the bravest.