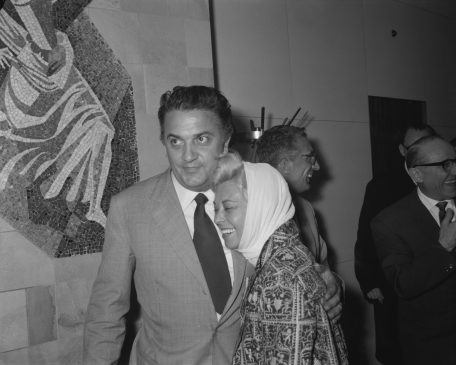

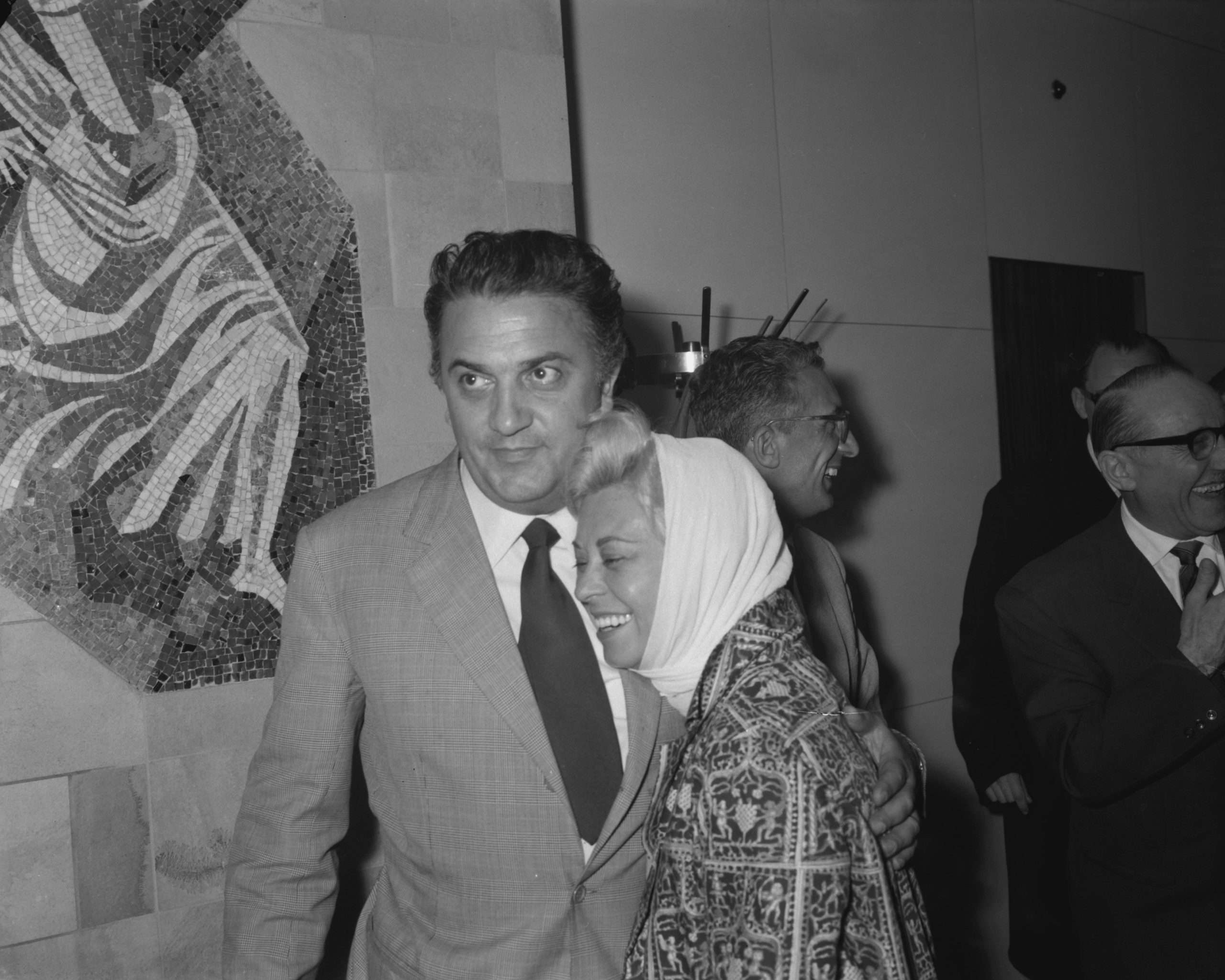

While other directors of the 1950s were busy filming the world as it was, Federico Fellini was the first to realize that the most interesting world was the one inside his own head.

As someone who has spent years deconstructing the “how” and “why” of filmmaking, I’ve found that you don’t just watch a Fellini film—you survive it. He was the great ringleader of a spectacular, surreal, and deeply personal circus.

The Great Divorce: Breaking the Chains of Neorealism

Fellini cut his teeth on the gritty, rubble-strewn streets of Italian Neorealism, co-writing the script for Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. But if you look closely at his early work, you can see he was already restless.

In my view, his 1954 masterpiece La Strada is the exact moment the “Felliniesque” was born. While critics at the time wanted a political statement about poverty, Fellini gave them a “poetic” spiritual allegory. He shifted the camera away from the social condition and onto the tragic frailty of the human soul. This is a distinction many modern summaries miss: Fellini wasn’t ignoring reality; he was simply arguing that our dreams are just as “real” as the dirt beneath our feet.

8½: A Technical Masterclass in “Director’s Block”

If La Dolce Vita was a cultural explosion, 8½ (1963) was a nuclear one. Having hit a wall of creative paralysis, Fellini did the unthinkable: he made a film about a director who couldn’t make a film.

From a technical standpoint, this is where Fellini’s genius shines. He utilized wide-angle 25mm lenses in tight close-ups, creating a subtle distortion that makes the characters feel both “grotesque” and overwhelmingly intimate. As a viewer, you feel the same claustrophobia as the protagonist, Guido.

My Personal Take: The legendary opening sequence—Guido suffocating in a traffic jam and floating into the sky—is perhaps the most honest 60 seconds in cinema history. It isn’t just a fantasy; it’s a visual representation of the “Auteur’s Trap.” When I first saw this scene, it redefined for me what a camera could do: it doesn’t just record action; it records anxiety.

The “Felliniesque” Blueprint: Life as a Parade

To understand Fellini is to understand his obsessions. He didn’t use actors; he used faces. He was a “painter with his canvas,” often building entire city blocks inside the legendary Studio 5 at Cinecittà just so he could control the exact curve of a nose or the shadow on a wall.

- The Circus Metaphor: For Fellini, life wasn’t a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. It was a parade.

- The Finale: Notice how his films often end in a procession. In 8½, the ending isn’t a “resolution” of the plot; it’s a celebratory dance where all his memories, mistresses, and enemies join hands. It’s a profound statement: we don’t “solve” our lives; we simply learn to direct the chaos.

Why Fellini Matters in 2026

In an era of mass-generated, “perfect” digital content, Fellini’s work stands as a reminder of the power of the imperfect, the bizarre, and the human. He gave directors like Martin Scorsese and David Lynch the “permission” to be weird. He proved that the universe within is far more vast than the world outside.