Key Takeaways: The Master’s Toolkit

- Suspense vs. Surprise: Hitchcock’s “Bomb Theory” defined modern thriller mechanics—showing the audience the danger before the character knows creates unbearable tension.

- The “Vertigo Effect”: He invented the “Dolly Zoom” (track back, zoom in) to visually replicate the physical sensation of falling/dizziness, a technique still used by Spielberg and Scorsese.

- Visual Voyeurism: In Rear Window, he turned the screen into a pair of binoculars, forcing the audience to become complicit “Peeping Toms” alongside the protagonist.

- The MacGuffin: He popularized the narrative device of an object (like the uranium in Notorious) that drives the plot but is ultimately irrelevant to the emotional story.

- Pure Cinema: Hitchcock believed dialogue was secondary; he constructed scenes so that if the sound failed, the audience would still understand the emotion through editing alone.

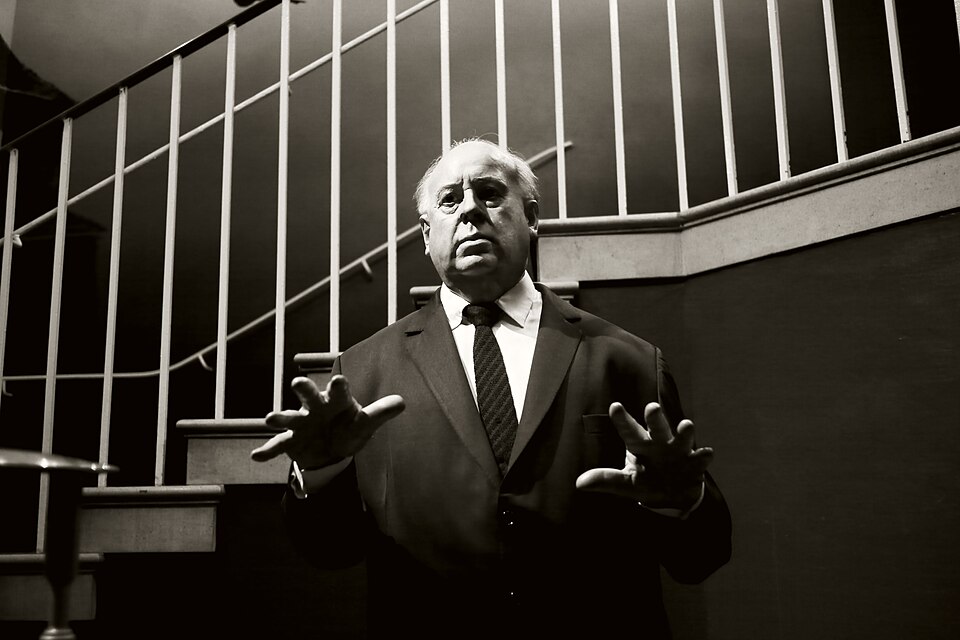

If cinema is a language, Alfred Hitchcock wrote the dictionary.

Before Hitchcock, thrillers were largely “whodunits”—puzzles to be solved by the end of the film. Hitchcock changed the game. He wasn’t interested in who did it; he was interested in how it felt to watch it happen. He didn’t film scenes; he filmed psychology.

For Celebrimous readers, understanding Hitchcock is not just about appreciating old movies. It is about understanding the source code of every thriller, horror, and mystery film released in 2026. He was the first director to realize that his true instrument wasn’t the camera, but the audience’s nervous system.

The “Bomb Theory”: Why We Wait for the Boom

The most critical lesson Hitchcock taught Hollywood was the difference between Surprise and Suspense.

- Surprise: Two people are talking at a table. Suddenly, a bomb explodes. The audience is shocked for 15 seconds.

- Suspense: The audience sees the bomb planted under the table first. It is set to go off at 1:00 PM. The clock on the wall shows 12:45. Now, the same boring conversation becomes excruciating. The audience wants to scream, “Stop talking and run!”

My Analysis:

This technique turns the audience from passive observers into active participants. We feel helpless. In Sabotage (1936), he uses this ruthlessly. Today, directors like Quentin Tarantino use this exact method (think of the opening scene of Inglourious Basterds—we know the people are under the floorboards; the Nazi officer does not).

Vertigo and the Invention of the “Dolly Zoom”

Vertigo (1958) is frequently cited alongside Citizen Kane as the greatest film ever made. But beyond its haunting story of obsession, it gave cinema a new visual word: The Dolly Zoom.

Hitchcock needed to show the audience what acrophobia (fear of heights) actually felt like. He didn’t want the actor to just look scared; he wanted the floor to drop out from under the viewer.

The Technical Execution:

He instructed his cameraman, Irmin Roberts, to do two opposing things simultaneously:

- Dolly Back: Physically move the camera away from the subject.

- Zoom In: Adjust the lens to zoom in on the subject.

The Result: The subject stays the same size in the frame, but the background wildly expands and warps behind them. It creates a disorienting, elastic visual that mimics the nausea of dizziness.

- Legacy: You have seen this in Jaws (when Brody sees the shark), Goodfellas (the diner scene), and The Lord of the Rings. It remains the most effective way to show internal panic on screen.

Rear Window: The Art of Voyeurism

If Vertigo is about obsession, Rear Window (1954) is about the guilt of watching.

Hitchcock confined the entire film to one room. The protagonist, Jeff (James Stewart), is stuck in a wheelchair with a broken leg, watching his neighbors through binoculars.

Technically, Hitchcock uses Point-of-View (POV) editing to trap us.

- Shot A: We see Jeff looking.

- Shot B: We see what Jeff sees (the neighbors).

- Shot C: We see Jeff’s reaction.

Why this matters:

We are never given an “objective” view. We only see what Jeff sees. When he becomes convinced a murder has happened, we are convinced too, even without proof.

Hitchcock is making a meta-commentary on cinema itself. We, the audience, are sitting in a dark room (the theater), spying on people who don’t know we are watching. In Rear Window, Hitchcock calls us out for being “Peeping Toms.”

Psycho: Shredding the Rules

In 1960, Hitchcock did the unthinkable with Psycho.

He took the biggest star in the film, Janet Leigh, and killed her 45 minutes into the movie.

The Shower Scene Anatomy:

This 45-second scene took seven days to shoot and features 78 camera setups and 52 edits.

- The Edit as a Weapon: The knife never actually touches the skin in the frame. The violence is created entirely in the cut. The rapid-fire editing matches the stabbing motion, assaulting the viewer’s eye.

- The Sound: The famous “screeching violin” score by Bernard Herrmann was originally not wanted by Hitchcock (he wanted the scene to be silent). When he heard the music, he doubled Herrmann’s salary. It proved that sound is 50% of the terror.

Conclusion: The Puppeteer

Alfred Hitchcock was known as the “Master of Suspense,” but he was really the “Master of Control.” He storyboarded every single shot before filming began; for him, the actual filming was just a boring necessity to get the images on screen.

He didn’t trust actors (“Actors are cattle,” he famously joked), and he didn’t trust dialogue. He trusted the image.

Final Verdict:

In 2026, when you watch a David Fincher thriller or a Jordan Peele horror movie, you are watching the children of Hitchcock. He taught us that the scariest thing isn’t the monster in the closet; it’s the camera that refuses to look away.